In June of 2024, I began working on The Federation of Worker Writers and Community Publishers (FWWCP) archive project, under the direction of Professor Jess Pauszek. Along with peers in both undergraduate and graduate programs at Boston College, I was tasked with making the archival materials of nearly four decades of FWWCP writing more accessible for prior members, scholars, community activists, and their families. The FWWCP began in 1976 in London, England and expanded across continents over the years as a writing and publishing network for working-class people. Throughout its forty-plus-year history, the FWWCP published thousands upon thousands of community publications by working-class writers in the form of poetry, prose, magazine, pamphlets, anthologies, newsletters, and more. While the FWWCP printed collection is physically located at London Metropolitan University within the Trades Union Congress Library’s Special Collections, the larger goal for this archival work has been about finding ways to increase access to these working-class publications and histories.

My role in the project was seemingly simple: For the better part of that summer, from June through August of that year, I found myself writing and revising summaries of texts from the collection’s London materials that Professor Pauszek had duplicate copies of here in Boston. On the surface, the job was simply a good way to help this project grow, earn some archival bona fides for my CV, and get some help paying rent while I was not teaching. But quickly, I learned that, beyond the material comfort that the work provided, the intellectual reward was nearly as important a benefit of the job.

Typing up decent summaries for the FWWCP archive’s database meant that I had to first read the texts that I was making more accessible for others. I must have read at least a dozen solo-authored books of poetry, penned by working-class people who had been told their verse, and especially its content, was not quality enough for polite society. Biographies about – and autobiographies by – people who reminded me of all the friends’ moms and dads, churchgoers, deli counter workers, and teachers I had grown up around in my own community kept my attention over the summer. I flipped through pages and pages of magazines that accounted for the collective work of folks whose artistic visions were spelled out over pints, whose writing clubs turned into community organizing events, whose international travel bridged the gap between working-class enclaves from rural England to the urban centers of America’s east coast cities. There were so many stories, real and fictive, that passed through my hands that summer. And, while some are easier to recall than others, one thing is clear: They are all worthy of being preserved and, perhaps more importantly, of being shared.

Such a revelation truly set in when I made it to the collection of Federation Magazine (FEDMag). More than any other kind of media I handled for the project, the FEDMag seemed like the clearest demonstration of community present in the archives. There, the FEDMag editorial team, over the course of a few decades, had undertaken a tremendously bold project to find, replicate, and preserve the actions and art from members of not just the Federation, but also from other groups like it throughout the world. It really did seem like the material manifestation of organizers who cared for and about one another and who were invested in showing the world that the lives of creatives who do not usually get the limelight matter too.

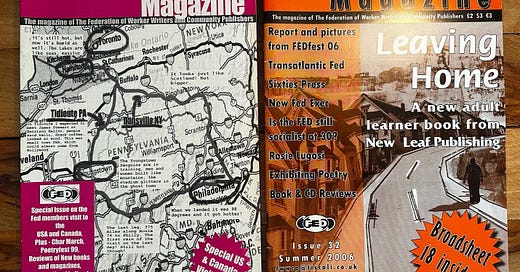

For instance, in the 18th issue of the magazine, printed in November of 1999, members of the Fed document a trip they took to visit working-class writers in America. There, Vie Lawrence-Grey, Roger Drury, and Richard McKeever, among others, capture just how – despite being separated by an entire ocean – worker writers in both the US and the UK both lived, work, and wrote about the same things: trouble paying bills, relationship highs and lows, the joy provided by writing, and so on. In another issue, printed six years later, topics like mental health and class politics are discussed, not at arm’s length as one would find in a more widely circulated paper, but rather with the care and dignity of people speaking to, about, and for common folk. Every issue contained stories like these. Each page I flipped through preserved a story a working-class person had to tell, a stanza they could not help but to compose, an opinion they knew would be thoughtfully confirmed or countered by other worker writers.

[caption: Federation Magazine Issues 18 & 32, from the FWWCP Archive project at Boston College.]

More than serving as a publication platform for writers who, I think it is safe to say, might have otherwise gone their whole lives unpublished, the periodical served, and continues to serve, as an archive in and of itself. For, without the magazine and these present-day efforts to preserve and digitize its issues, who is to say what would happen to the tangible evidence that working people lived the kind of life that could not be reduced to the paystubs they received, or the scattered bills they may have left behind? What would happen to the writings they made?

While it hit me rather quickly that the FWWCP’s materials should not only be preserved but also be made accessible for today’s audiences, this project’s personal impact became further cemented earlier this year. In January, after living a tumultuous, yet beautiful, life, my grandmother passed away at the age of 74. Her death was not a surprise: since November of 2023, my family knew she had inoperable cancer. Over the year and a few months between her diagnosis and her passing, my grandmother and I spoke regularly about her life, the people she grew up around, the places she lived and visited, and the people she loved. Looking back, I realize now that she had seen it as her responsibility to pass along those unwritten, loosely bound stories of people who, in the absence of their own FWWCP, had had their rich lives fade into obscurity so often. So it goes in longstanding working-class communities.

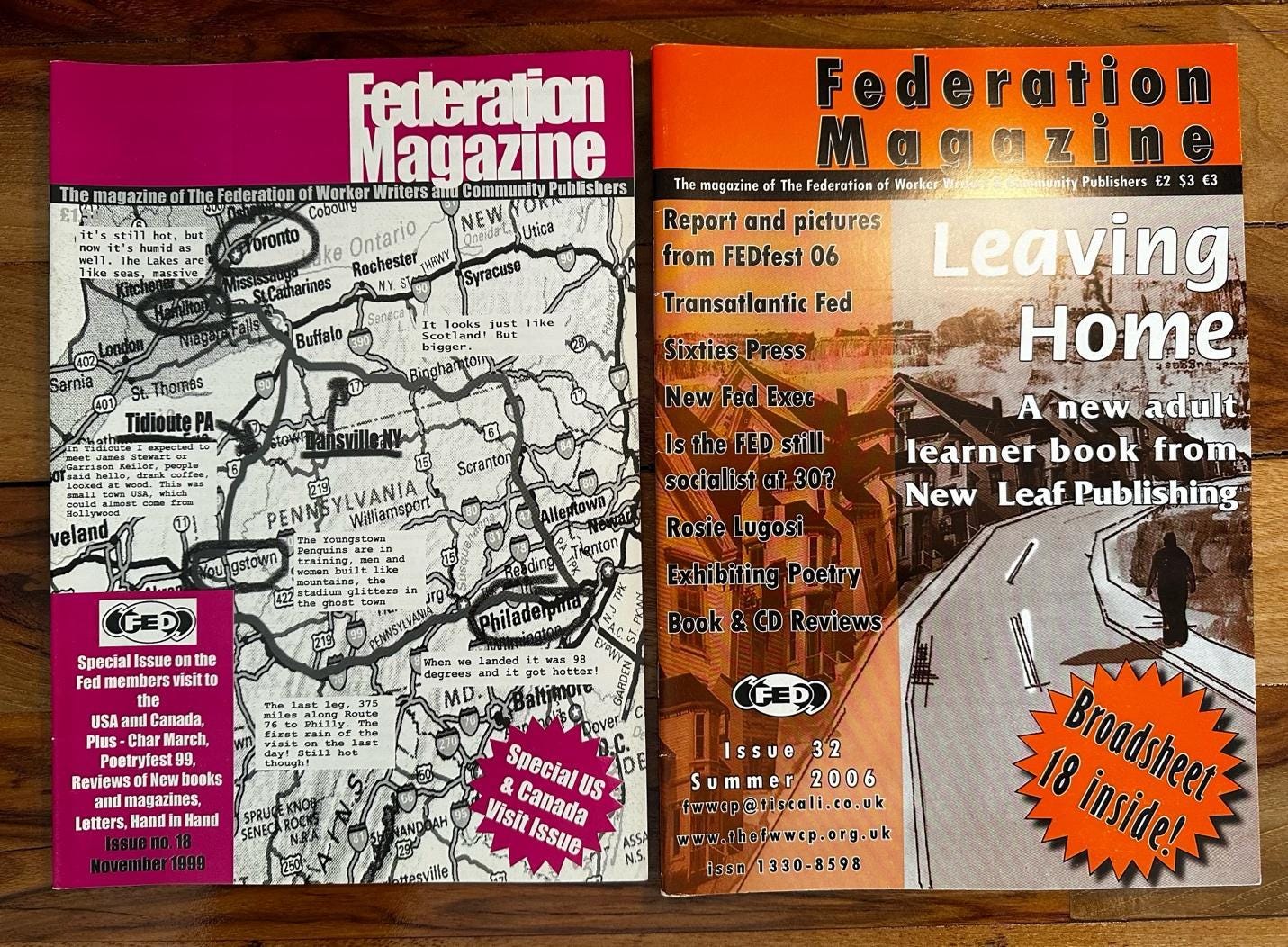

At the same time that my grandmother passed along the stories that she had been tasked with safekeeping, she was also giving me her physical archives. Family photos, roadside truck stop trinkets, birth, death, and wedding certificates, deeds to plots no longer belonging to her relatives – it all passed from her hands into mine. With these materials came the proof that folks not too different than those FWWCP members who filled its published texts with their stories, lived and breathed the same as I do, the same as my grandmother had. That community of workers from rural West Virginia was no different from the countless stories I read and catalogued about people living and writing in rural England. But this was not a realization I had until after my grandmother had passed. I had been fortunate enough that she had the foresight, in her final days, to make me the family archivist. Had she not taken that step, who is to say what would have come of those possessions that I am sure, in some cases, are the only tangible remains of long departed members of my family? It made me wonder: How many times have contributors to the Fed come and gone with little proof – outside of their published prose and poetry – that they had lived lives worth writing about?

[caption: An assemblage of family photos, military service records, a marriage certificate, and a short story my grandmother wrote after high school, from my family archive.]

Many of the Fed’s founding members have passed away. While they lived storied lives – ones that did not need approval from the upper echelons of those with more ‘class,’ or money, or education – their materials, which now make up the foundation of the organization’s archives, may very well be all that is left for some. Without the benefit of a tenure track position that ensures a university will keep their papers, an elected office that makes their documents state property, or a cushy C-suite job that guarantees all their pricey possessions are preserved by wealthy benefactors or buyers, the members of the FWWCP would otherwise be archive-less – and so, too, would the tangible evidence of their meaningful lives.

In the same way that I now know the importance of preserving and sharing my grandmother’s archives, I also recognize the unspoken importance of the FWWCP’s archives. This is not just a project for scholars. It is an effort to make sure those who worked so hard to be heard and read, have their voices amplified to echo for generations to come.

-

This reflection would be incomplete without an acknowledgment that the aforementioned experiences have also had an impact on my scholarly work. Given that I am working on a dissertation about the role of printed material in the South during the nineteenth century, I spend a good amount of my time either in archives, or on their digital websites. During these deep dives, while I am looking for primary source materials to write about, I will often come across documents that give brief glimpses into people’s lives: Pamphlets about the inner workings of church life, broadsides denoting shifts in political sentiments, newspapers advertising the sale of enslaved people and books alike. For the most part, parsing through these archives has always been a directed activity for me. I always set out with sources in mind, and I cut through a lot of content to find them – meaning I do not always stop to think about all those stories I miss out on.

Now, after having been through both the professional and personal experiences of seeing the archive’s power to preserve everyday lives firsthand, I move a bit slower. I do not pass by the tracts on niche, largely inconsequential local governance; I do not overlook the broadsides announcing the entertainment accessible for nineteenth century audiences; I do not take the fugitive slave notices for granted. All these things attest to the very real lives lived by past humans. Humans like those who made up the Fed. Humans like my grandmother. And humans who, were it not for archives, would have left no lasting written trace.