Building a Digital Archive with Student Researchers

Have you ever wondered what research looks like in an English department?

By Jessica Pauszek; contributions from Emma Janda and Hannah Bell

Have you ever wondered what research looks like in an English department? Believe it or not, research in English is actually quite varied (take a look at the department’s faculty pages and you’ll see!). In fact, most of us are researching and developing multiple projects at a time. But today I’d like to share a bit about what my current research looks like and how students have been collaborating with me for the past year and a half at Boston College. We’ll also hear a bit from some students reflecting on their research experiences.

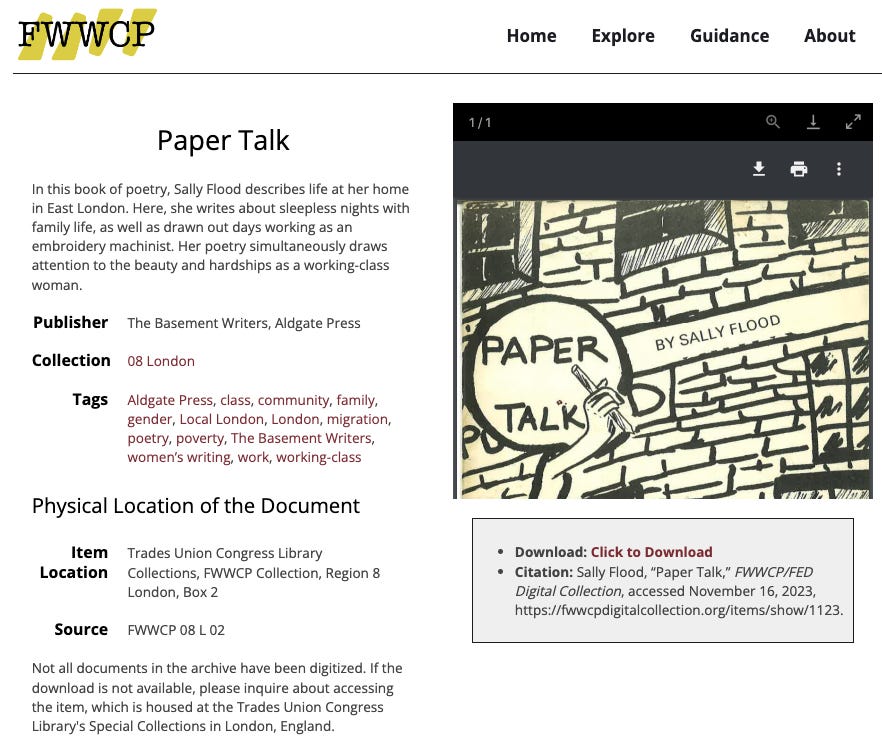

When I consider my own learning, the most meaningful moments have been when teachers (or professors, parents, coaches, etc.) helped me realize my own agency. Learning, in these moments, wasn’t just about passively absorbing knowledge; rather, it was about having a chance to be an active participant and learn through doing. That is what drew me to my specific field of Composition and Rhetoric: I wanted to learn how writing could do something in the world and have a social impact. At Boston College and beyond, research in Composition and Rhetoric ranges extensively – from working with homeless communities to developing contemplative writing practices (Prof. Mathieu) to researching industrial archives such as the Ford Motors English School or exploring best practices of writing fellows/tutors across institutions (Prof. Portillo) to analyzing zines written by feminist activists and using zines as teaching tools (Instructor Noël Ingram). My own research is focused on developing print and digital archives of the Federation of Worker Writers and Community Publishers (FWWCP), as well as highlighting how this network used writing for social change. The FWWCP was a working-class writing and publishing network that began in London, England, in 1976 and grew to include over 120 writing groups from countries across the globe. If you’re interested in reading about my work building a print archive in London at the Trades Union Congress Library, you can read more here. But for now, I'm going to focus on the digital archival which is in progress at fwwcpdigitalcollection.org.

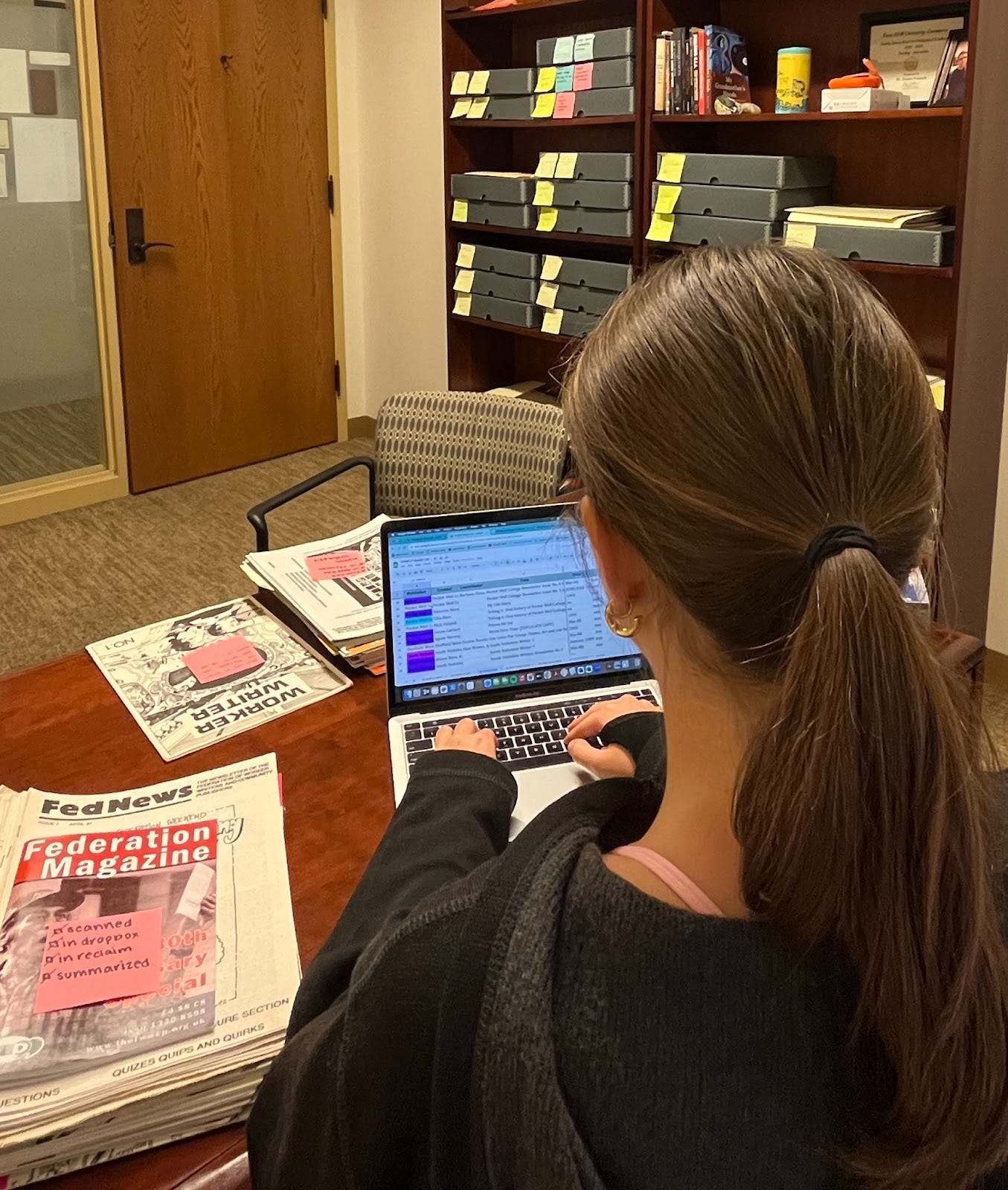

It takes a ton of time, labor, technological expertise, and money to develop digital collections. Thankfully, in 2022, I was awarded an Academic Technology and Innovation Grant, which provided me two years of funding to expand the digital archive that I began years ago. I’ve been able to bring in undergraduate and graduate students to collaborate on this work. Our goal has been to digitize publications and develop specific metadata so that students, scholars, and community members can all explore the collection. When we scan physical materials, create PDFs, and then write descriptions of these materials, we are producing content for the digital archive so that viewers have access to these documents and can see background information about the author, date of publication, geographic location and more. Instead of these documents sitting in my office, we are able to make them more accessible to researchers, students, and even family members of the FWWCP members who want to see writing created decades ago by someone they knew.

Emma Janda, a junior political science major and American studies minor, and Hannah Bell, a sophomore neuroscience major, have been doing this work for the past year and a half. Here are some of their reflections about what they’ve found interesting and learned from participating in this research.

[photo of Emma and Hannah standing in front of some acid free, clamshell archival boxes, which we use to store the archival documents]

Emma:

When Jess [Professor Pauszek] asked Hannah and I to do research with her, I really had no clue what I was getting myself into. I looked for an on-campus job when I first transferred to BC in the fall and came up with nothing, so when this opportunity became available - I was thrilled. I had just finished taking Jess’ First Year Writing Seminar class and loved how she intertwined her passions with class material. I knew we would be doing archival work, but I did not know the full extent or the impact it would have on me. What I love most about this research is you never know what you are going to uncover or learn that day. Some days, I’m looking over compelling minutes of the FWWCP meetings, which are filled with debates over socioeconomic status, gender, and/or identity. Other days, I’m deepening my cultural understanding of the world through reading and summarizing FWWCP publications in various forms (poetry, memoir, op-eds, pamphlets), or I’m digitizing these working-class texts with the scanner.

[Photo of Emma putting an archival box back so that we keep them in order]

No matter what task I may be doing, it has been fulfilling for me to think about the influence my research at BC can have on a broader community. What is dubbed as “research” for us isn’t solely contained in an office space in Stokes Hall; in actuality, it has an audience both within and beyond the university. For instance, through this work, we are able to showcase and credit individuals whose writing might otherwise be lost, because they were never archived before. Luckily, we are building an archive! In fact, even since we started working with Jess, we have had community members from England and scholars from Australia, the U.K., Ireland, and the U.S. get in touch about using these materials to teach from and guide their research (on topics such as miners’ strikes, translingual writing, class identity, and community publishing).

Doing archival work has helped me reflect on my own background and opportunities I’ve been given coming from a white middle-class family, and what I can do with this privilege and experience. Not everyone has the opportunity to attend a school like Boston College, but that does not make these individuals any less of a person, writer, or learner. I like to think that the work we’re doing is slowly breaking down barriers and taboos surrounding education, class, and what it truly means to be a “writer.” Research isn’t just about typing questions into a search bar or taking detailed notes on a particular subject, but about uncovering meaning, piecing together information, and using what you learn to reflect on yourself.

[Photo: Emma scanning publications with a CZUR scanner and saving them into multiple file formats so we have more than one copy]

Hannah:

As a part of my work with Jess, Emma, and the Federation of Worker Writers and Community Publishers, I have been reading, writing descriptions, and digitizing a variety of autobiographical and fictional stories, anthologies of poems, magazines, and newspaper articles. These documents range in theme, geographic location, writing style and authorship. Some books describe family recipes or cultural traditions around the holidays, while others discuss workers' rights and the literacy gap. What I enjoy most is that each story, poem or article is distinctly unique and I never know what to expect. When summarizing a text, I am able to piece together information about someone’s life, educational experience, or individual perspective that cannot be found in my neuroscience textbooks.

Our research process is ongoing. Once I draft a description, Emma and Jess review these and comment on them so that we can revise our writing. But the process doesn’t end here. In order for us to get this information up onto the archive, we have to digitize the document, save it in multiple file formats on at least three platforms, and then update an enormous spreadsheet with author information, location details, word tags, and many more categories. After each of these pieces are complete, Jess uploads the spreadsheet information to the website and these digitized documents and our summaries become searchable content and public for viewers. I have learned that creating a digital archive is more than compiling documents, but instead requires detailed organization around the management of digital data. I have learned how to navigate the “back sites” of research databases, something which has made me appreciate the work involved in creating other public research sites that I can then use for academic research in classes.

[Photo of Hannah updating the massive spreadsheet where all the metadata is collected. We color code our work in it so we know who is actively working on sections]

Before my work with the FWWCP, I viewed research as simply a combination of lab coats, test tubes and maybe some chemicals. However, archival work has taught me that research exists beyond laboratory settings and instead can be seen as both a celebration of writing and a service to making lesser-known histories public. I have greatly enjoyed my archival work, as each piece gives me a unique insight into global writing and various aspects of the human experience. Each working-class writer expresses thoughtful and impactful sentiments about their lived experience. Emma and I also see how our work can impact others as we develop descriptions, so we try to convey the writers’ hard work, energy, and testimony into our summaries of each document. I have learned that every step of our research, no matter how big or small, can have a real, tangible impact on people’s lives outside the bubble of Boston College. This sentiment has broadened my idea of what it means to do research.

[Photo of the FWWCP Digital Collection, with the metadata and search information for Paper Talk by Sally Flood]