Archives in Action Across the University

By: Jessica Pauszek, Ashlyn Stewart, Emily Kent, Carina D’Urso, and Mackenzie Daly

When I (Jess) began preparing for my fall 2024 course called Archives In Action, I was working closely with the Libraries’ Digital Scholarship Group. In particular, Melanie Hubbard, Ashlyn Stewart, and David Thomas were (and still are) helping me build the FWWCP Digital Collection, thinking through digital humanities work such as developing metadata, digitizing archival documents, geospatial mapping, and more. I started asking Ashlyn, a digital scholarship specialist, whether she would be interested in joining us for a session or two of this course. However, I didn’t realize we could collaborate more than that. In the end, we co-developed and co-taught this course with 15 graduate students and 2 undergraduate students. Our collaborative teaching strengthened every step of the process, from creating the syllabus to bringing in print and digital archives as examples to helping students with final papers, because we each had different perspectives on archives and different experiences helping students learn to use them. We decided to write this post to showcase the ways this course allowed us to collaborate across the university (and beyond it!) with students, faculty, and staff in various disciplines and areas of expertise.

As we went through the semester, Ashlyn shared her expertise in digital archives, teaching students to find, evaluate, and navigate archival collections online. She also demystified the process of creating online collections, allowing students to try hands-on activities in developing metadata and data visualizations. In the end, nearly half of the students in the course chose to include a digital element in their final projects.

Through my (Jess’) ongoing work with the FWWCP, I demonstrated the importance of working with various communities through archival projects. We discussed the ethics, labor, time, and materiality involved in preservation projects – as well as the very real and tangible ways that projects can stall out or move forward based on resources. We discussed archival methods, looked at archival materials, and explored how to teach with archival materials as well.

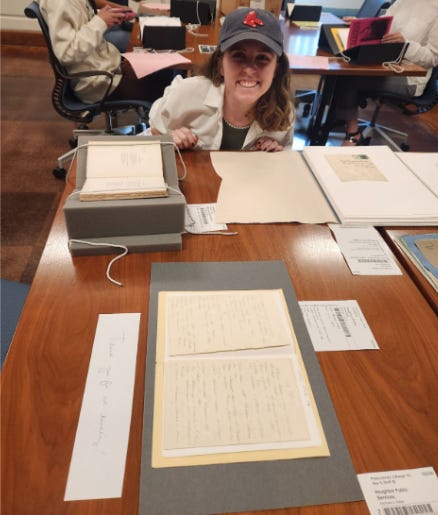

In our course, the physical and digital were not at odds. Instead, they were two tools with different benefits and limitations that students could use to advance their knowledge. We brought in additional collaborators to speak to the physical and the digital, as well. Amanda Ferrera from the Burns curated materials for our students to explore, and Melanie Hubbard from the Digital Scholarship Group discussed writing and designing for the web. We also visited Harvard University’s Houghton Library, with an exciting session led by Christine Jacobson, the Associate Curator of Modern Books and Manuscripts.

A goal for both of us (Jess and Ashlyn) was to help students see the value of archives for their own research. While we of course wanted students to gain practice in reading and analyzing archival documents, our main hope was a step further: we wanted students to learn to ask research questions that leverage archives. For the final paper, we asked students to identify archives that were relevant to their scholarly interest and practice integrating those into their own scholarship. This was a big shift for the students who are used to working only within the primary literary text they study, but together we all learned how additional archival sources can complement inquiry in both literary studies and other fields within and beyond the English department.

We asked three PhD students, Emily Kent, Carina D’Urso, and Mackenzie Daly to share a bit about their experiences with archives from this course:

The Invitation of the Archives (Emily Kent, PhD Student in Formative Education)

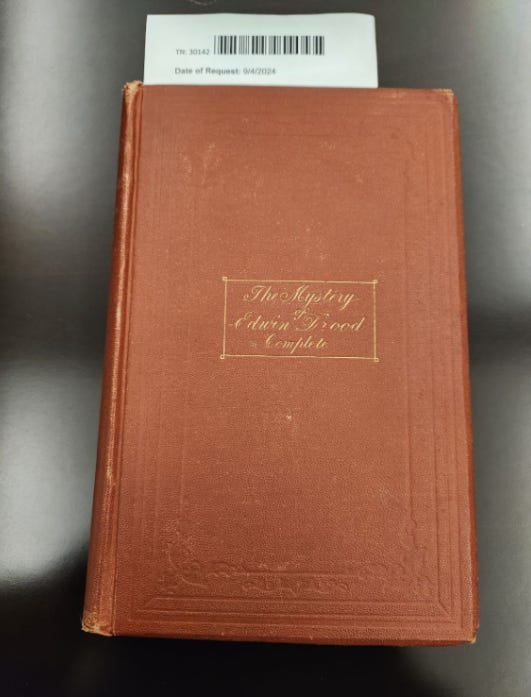

When we first stepped into the Burns Library, it was early in the semester. Our class was still getting to know one another, and as many an introduction goes when pursuing graduate studies, we were asked to share our names and our areas of interest. The goal for the day was to analyze one of the artifacts made available to us and its rhetorical context, and like a “good” doctoral student, I focused initially on pieces that aligned with the short description I gave in my introduction. Then, Mandy asked if anyone would be interested in seeing an older copy of The Mystery of Edwin Drood, and my head turned.

Edwin Drood holds a special place in my heart as the final, unfinished novel of my favorite author and as a high school graduation gift from my favorite teacher and mentor. For me, this book evokes the power and promise of unfinished stories, and the copy I held that day in the Burns claimed to be finished by a medium, imparting Dickens’ words from beyond the grave. It offered me answers and new mysteries, and I gave it my full attention.

As I researched it, I learned about spiritualism; a highly debated, 19th-century publisher in Vermont (T. P. James); and how Dickens’ final piece has been approached across time to complete it. For many, including James, the novel was a magnet, a challenge to know the unknowable. For me, it was an invitation, not only to attempt to understand the unknown but to consider how my own interests, knowledge, and intuitions could inform my research. If I hadn’t been familiar with the novel when I saw it in the archive, I wouldn’t have understood what made this copy unique. What I brought to the archive informed what I was able to learn from it, which might seem straightforward but was the crux of my struggle entering my doctoral studies. I questioned how to bring myself into my research, when much of what I knew of doctoral work up to this point situated reliability as an absence of the researcher. My afternoon in the archives transformed a copy of a mystery novel into a mystery itself and what had been ingrained in me as a threat to reliability, or even superfluous, into a unique strength and positionality.

I brought this affirmation with me into my final project, which incorporates archival research into a unit on John Lewis and Andrew Aydin’s March. In this unit, students would read the graphic novel and engage with institutionally curated and community-based archives as well as a variety of artifacts: photographs, oral histories, primary source documents, and more. I believe that literature can be transformative, offering us an opportunity to better understand ourselves and others, and after my experience in the archive, I am curious how incorporating archival research and materials may help students further connect with real-life people who drove its story. As I look ahead in my studies, I wonder: What experiences allow students to be transformed by literature and other art forms? How might we as educators support them in this? And, how might these experiences further connect us as people?

What makes an archive public? (Carina D’Urso, PhD student in Formative Education)

As an art museum educator, I believe deeply in the power of objects to evoke curiosity, to bolster critical thinking, and to cultivate empathy. For me, archives are public spaces capable of cultivating meaningful learning and engagement. As a result, I am perpetually challenged by the barriers to entry surrounding them. As collection-based institutions, these spaces signal what is worth knowing to visitors, uplifting particular types of social and cultural capital and devaluing others. Archives in Action enabled me to critically examine archives as “power-laden” spaces, as Katrina Powell describes. In visiting a wide array of spaces, from the Burns Library, to the Houghton Library, to a multitude of digital archives, and interviewing the archivists and educators behind these spaces, I was exposed to a variety of approaches to engagement and accessibility.

For my culminating project, I returned to my roots in Brooklyn, New York to conduct an analysis of the Interference Archive, a volunteer-run community archive that was first introduced to me while I was an undergraduate student at CUNY Brooklyn College. The archive centers the relationship between cultural production and social movements, welcoming public participation through its open stacks archival collection, publications, study center, and public programs including exhibitions, workshops, talks, and screenings. Unlike most collection-based institutions, at the Interference Archive, visitors can touch exhibited objects as they explore, a great affordance given that many of the archived materials were originally produced and designed for wide distribution and interactivity. In reviewing one of their publications, I discovered a photo of a sign outside of the archive which read “Interference Archive: Library and Social Center.”

I was instantly reminded of the Italian phenomenon of centri sociali, self-organized social centers, unoccupied buildings where activists meet and sometimes live as squatters. Through literature review, object analysis, and observation of public programs, I began to examine the history of this category across time and place. As Anita Lacey describes, “social centers are concrete manifestations of activist networks.” To witness this description in action, I immersed myself in the archive’s operations, even joining their Education Working Group in order to participate in the planning of a political education event. Browsing the collection, which contains objects created to further the mobilizing of social movements, such as posters, flyers, publications, zines, books, T-shirts and buttons, moving images, audio recordings, and subject files, amongst other miscellaneous materials, in search of threads related to the present political moment. One such example is a poster from the War Resisters League titled “It’ll be a great day.” Accompanied by a child’s drawing of a ship, the poster reads, “It’ll be a great day when our day care centers have all the money they need and the navy had to hold a bake sale to buy battleships.” Archival ephemera was activated as a springboard for reflection, dialogue, and the sharing of local mutual aid resources, which participants compiled on post-it notes peppered along the walls. I watched as the very space of the archive transformed, molding itself around the needs of the visitor.

At the Interference Archive, a world of inspiration awaits, and visitors themselves hold the key. As I look ahead to my future studies, I ask myself: What makes a space public? How do public archives, such as the Interference Archive, define “community?” How do archival spaces mediate interactions between visitors and the materials they steward? Who owns these records of history? Who decides?

Early American Literature and the Archive (Mackenzie Daly, PhD Student in English)

As a student who studies Early American literature, archives are central to my research. From leafing through the pages of a first edition of The Coquette (1797) and reading Cotton Mather’s letters to examining the way that the archive is organized—who gets included and why? Archives help us to better understand the past and the present.

The final project for this class provided me with the opportunity to explore some materials which I had been interested in for a long time—archives of obituaries printed in newspapers. Although the subject matter is obviously grim, obituaries offer an interesting lens into how lives are recorded: Who gets remembered and how do we remember them? My research specifically focused on the obituaries of Henry Obookiah, one of the first Native Hawaiians to be converted to Christianity. Under the pretense that he would receive an education, Obookiah sailed to the United States and eventually wound up in Connecticut where he became a part of the Foreign Mission School—a school which sought to evangelize individuals from non-Christian countries with the intention of sending those individuals back to their homes to act as missionaries. Obookiah was well known in New England, not only for his involvement in the Foreign Mission School, but for his exceptional piousness. There was a vested interest in his future success as a missionary in Hawai’i, but Obookiah would unfortunately never make it back to his home country as he contracted and died of typhoid fever at the age of 26 in 1818. However, Obookiah’s deathbed scene as it was recorded and distributed through his Memoirs and obituaries, was so exemplary of what would have been considered a ‘good death’ to pious New Englanders that enthusiasm for the evangelization project in Hawai’i was bolstered.

Given the role that Obookiah’s death played in American missionary trips to Hawai’i throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, I was interested in studying the rhetoric and demographic of his obituaries. To get a better understanding of the obituary as a genre in the early 19th century, I transcribed and compiled 25 obituaries from 10 different Boston newspapers from 1804 to 1818 and used digital tools to search the documents to find frequently occurring words and phrases. I then found every iteration of Obookiah’s obituary and made note of what newspapers these obituaries were printed in and where in the newspaper the obituary was printed. Additionally, I compared the rhetorical style of Obookiah’s obituary to those I had compiled earlier and found that his differed greatly. Unlike other obituaries, Obookiah’s detailed his deathbed scene—a written account of pious deaths which were popular among many New Englanders. Deathbed scenes were printed individually on pamphlets, not in obituaries—so why was Obookiah’s different? How might wide-spread dissemination of the story of his pious death have contributed to the mythmaking around Obookiah, and, more broadly, the American evangelization project? This project encouraged me to think more seriously about what is included and excluded from the archive and consider the kind of value judgments we ascribe to different materials. What happens if we more closely scrutinize frequently overlooked materials like obituaries and other kinds of ephemera? What kinds of stories can they tell?